News

Sinar Mas Group: Destroying orangutan and chimpanzee habitats in Indonesia and Liberia for palm oil

Since 2019, banks have provided more than US$4.5 billion in forest-risk pulp and paper-attributable loans and underwriting services for RGE’s operations in tropical forest regions. Its creditors span the globe from China to Brazil and from the Netherlands to Indonesia. However, none of the financial institutions assessed has adequate policies in place to protect the forests and the communities that rely on them for their livelihoods for the negative impacts of RGE’s pulp and paper operations.

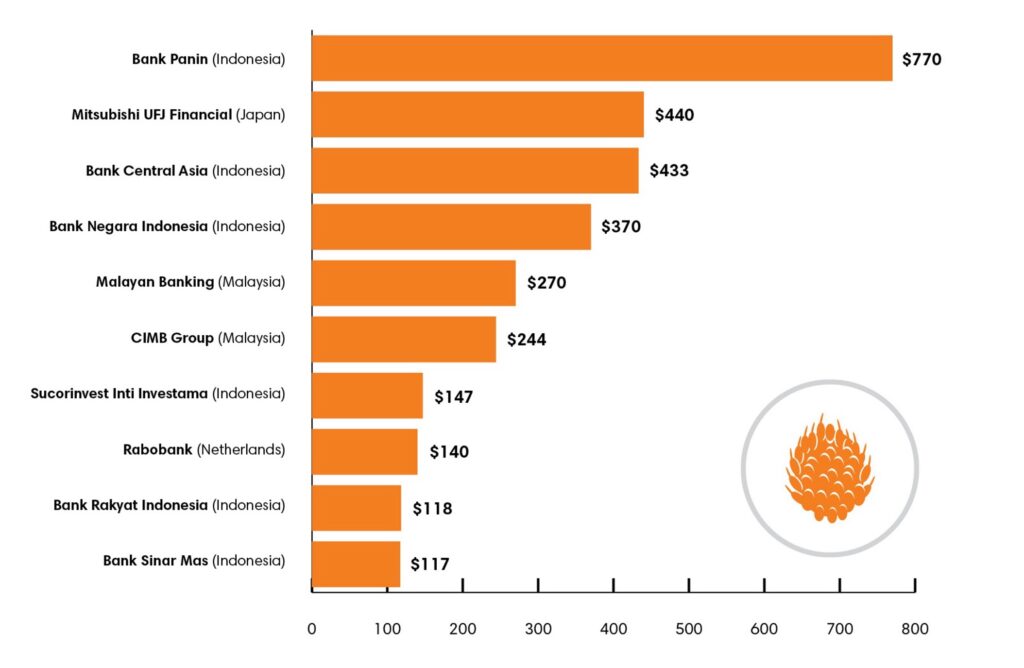

Largest 10 creditors to SMG’s palm oil operations (2019-2023 September, US$ millions)

Deforestation rates in Indonesia have steadily declined since the height of rampant clearing around 10 years ago. This is largely attributed to moratoria in some sectors, improved law enforcement, and improved supply chain standards as major commodity producers adopted no deforestation, no peat, and no exploitation (NDPE) commitments. Yet there are signs that forest loss in Indonesia is starting to pick up again, with a 16% increase from 2021-22, now standing at over 200,000 hectares per annum.

The nature of deforestation is also changing. Instead of major flagship plantation companies being the face of deforestation, it is now typically undertaken through low-profile entities which are still under common control with major producer companies. These “shadow companies” are not acknowledged as part of the same corporate group as the flagship entities, with common control obscured by complex corporate structures, secrecy jurisdictions, and nominee shareholders. These obscured relationships also appear to benefit banks and investors with narrow interpretations of what parts of client group operations are considered material to bank due diligence standards.

Such a pattern is evident in the operations of Royal Golden Eagle Group (RGE), a Singapore-headquartered natural resource group controlled by Indonesian tycoon Sukanto Tanoto. The group’s main operations are in Indonesia; however, it also operates production and processing facilities in Brazil and China. Historically one of the largest drivers of deforestation in Indonesia, RGE now projects an image of sustainability to its financiers and the international buyers of its pulp and paper and palm oil products.

In 2015, RGE’s flagship palm and pulp divisions publicly adopted NDPE-aligned policies. RGE also states it aims to achieve “net-zero” emissions from land use by 2030 and secured US$3.25 billion in sustainability-linked loans in 2021-2022 alone, citing its sustainability commitments. Major creditors include banks with commitments to no deforestation such as Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group.

Yet recent investigations show that a number of companies believed to be under common control with RGE group are among the largest drivers of deforestation in Indonesia, including the conversion of over 26,000 hectares of natural forest into industrial tree plantations between 2016-2021. In 2022, they cleared a further 7,000 hectares and over 1,000 peatlands. In 2021-22, wood fiber from one such company that had cleared forest was shown to have been shipped to RGE’s pulp mill in China. Another company under common RGE control is constructing a new mega-scale pulp and paper mill in North Kalimantan that will consume over 3 million metric tons of wood fiber a year and threaten to drive creation of new forest plantations in Indonesia’s intact forest areas in Kalimantan and Papua.

In response to these allegations RGE denied that these entities are under common control of RGE. RGE further stated that its business groups operate in accordance with its Sustainability Framework, which includes explicit no deforestation commitments, and that it has ambitious 2030 sustainability targets that aim to contribute to the achievement of national and global goals on climate, nature protection, and sustainable development.

To counter the threat posed by complex corporate groups, the Accountability Framework Initiative (AFi), an initiative to establish consensus on sustainable supply chains, recommends financial institutions define “a company” as the entire corporate group, meaning “the totality of legal entities to which the company is affiliated in a relationship in which either party controls the actions or performance of the other.” Applying recent due diligence guidance designed to determine corporate control indicates a high risk that the shadow entities above are under common control with RGE Group. As such, RGE’s creditors, including those issuing billions in sustainability loans, are exposed to serious deforestation and associated risks.

Secret corporate control of the natural resource sector is a critical question for governments, regulators, and industry. The AFi definition of corporate group has now been adopted by the Forest Stewardship Council and promoted as a due diligence principle for banks seeking to eliminate deforestation finance. Failure to apply policies at this level will have material impact on financiers’ exposure to environmental and other risks.

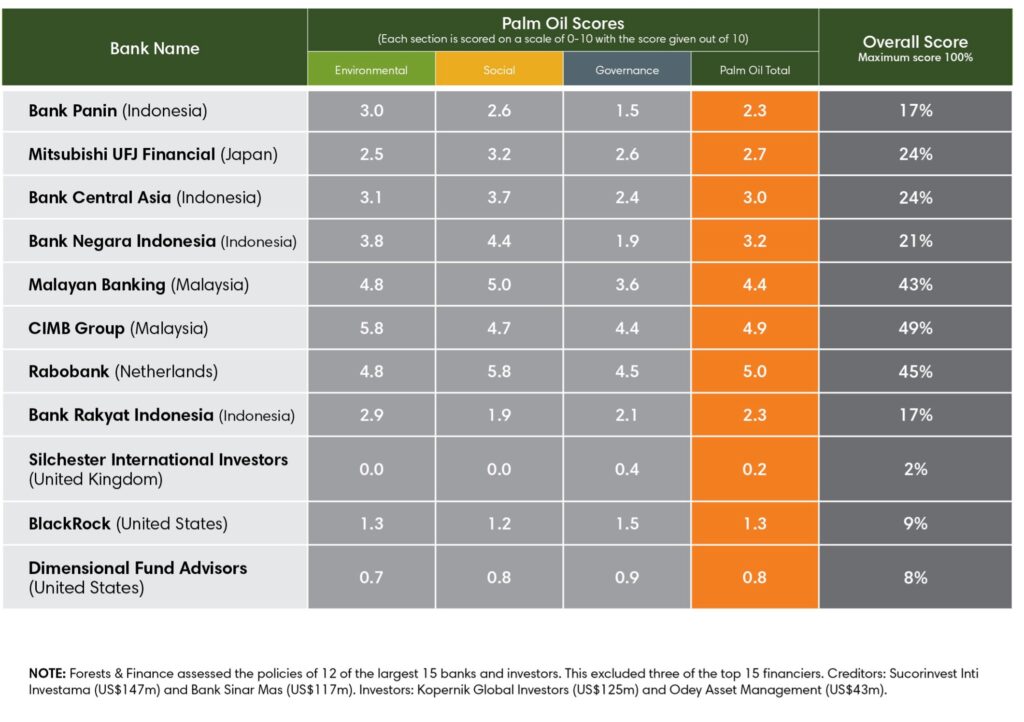

How do the bank’ policies stack up?

Overall, the strongest overall policy scores were by Malaysian banks CIMB (49%) and Maybank (43%) and Dutch bank Rabobank (45%). These three banks also scored highest for the palm oil sector, each scoring over 50% for either environmental or social palm oil criteria. While this sets them ahead of their peer lenders to SMG, it still demonstrates a failure by these banks and the wider financial sector to adequately address the ESG risks prevalent in these sectors. Given the repeated allegations against SMG for links to deforestation, peat drainage, and human rights abuses through its supply chain, these banks should be conducting enhanced due diligence and implementing non-compliance protocols in cases which violate their policies.

The creditors with the weakest policies are Indonesian banks Bank Panin (17%), BRI (17%), BNI (21%), and BCA (24%), and Japanese bank MUFG (24%). It would appear that these banks are doing almost nothing to limit their role in financing deforestation and human rights abuses as their policies are incredibly weak. The largest creditor to SMG, Bank Panin, and Indonesia’s largest bank, BRI, had higher scores for the palm oil sector than their overall scores, both scoring 2.3 out of 10. It is notable that BRI was the lowest scoring creditor on social criteria for palm oil. An analysis of SMG’s policies on Free, Prior, and Informed Consent policies found them to be inadequate, which means that banks are likely facilitating land conflicts through their financing.

Investors in GAR’s bonds and shares all have woefully poor policies, all scoring under 10% overall. It is extremely concerning that investors like BlackRock, which is the largest asset manager in the world with over US$9 trillion in assets under management, has only the most rudimentary ESG policies.

For cases like SMG, it is extremely important for financial institutions to apply their policies across the entire corporate group based on the Accountability Framework Initiative’s definition. This is crucial to ensuring they do not enable non-compliant subsidiaries or affiliates to access finance without reforming their practices.

Policy scores of SMG’s largest creditors and investors