News

Investigation: Dutch, Japanese pension funds pay for Amazon deforestation

By Fernanda Wenzel, Naira Hofmeister, Pedro PapiniOriginally published by ((o))oeco in Portuguese and by Mongabay in English

- Two pension funds in the Netherlands and one from Japan have invested a combined half a billion dollars in Brazil’s top three meatpackers.

- These investments in cattle ranching, an industry that’s the main driver of Amazon deforestation, contradict the environmental stances of the respective funds and their national governments.

- The fund managers and other experts say maintaining their stake is a more effective way of pushing for change in the companies than simply dumping the stock.

- But there’s also a growing realization that continued exposure to environmental risks over the long term will incur not just ethical and reputational harm for the funds, but even financial fallout.

For citizens of the Netherlands and Japan, the dream of a comfortable retirement is fueling an environmental nightmare in the Amazon.

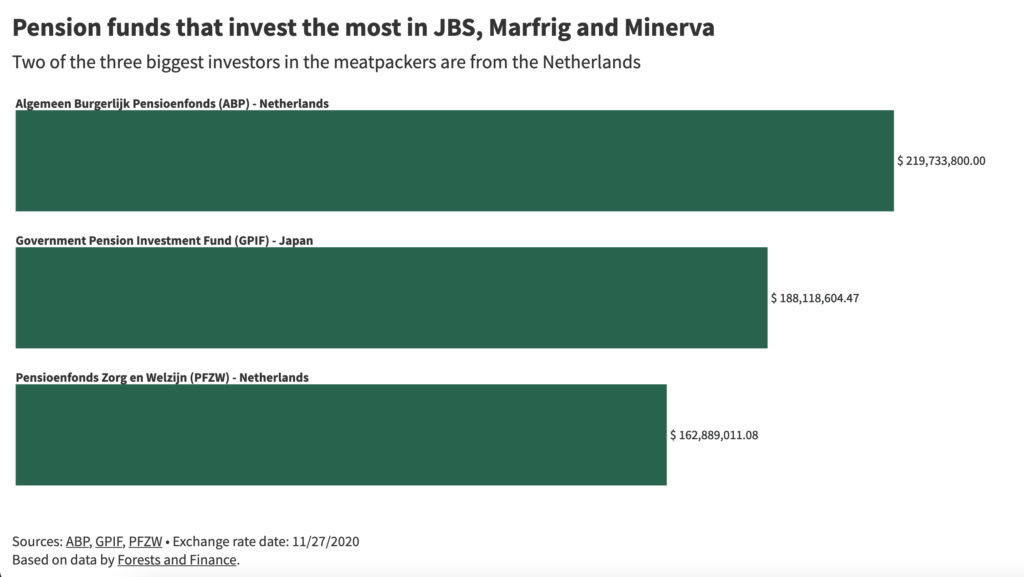

Three of the biggest pension funds in thse countries, catering to public employees and professionals, have invested a combined $571 million in Brazil’s largest meatpackers. These, in turn, are companies that operate in the Amazon, buying cattle raised on farms that have been illegally deforested. The sum invested by the Dutch and Japanese funds — Algemeen Burgerlijk Pensioenfonds (ABP), Pensioenfonds Zorg en Welzijn (PFZW) and the Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF) — is more than the entire 2021 budget for Brazil’s environment ministry, which has been slashed to 2.9 billion reais ($530 million).

And these are just the funds that we know of, says Ward Warmerdam, senior researcher at Profundo, a Dutch NGO that advocates for greater environmental sustainability in business. Few pension funds open their portfolios to public scrutiny, he says. “It is a sector with a large black hole. In most parts of the world, you don’t know where your retirement money is being invested.”

Pension funds are heavyweights on the financial markets because they control and determine the destiny of resources belonging to large numbers of people. “Of the institutional investors [that administer third-party resources], they are the largest,” says Cole Martin, an analyst at Fitch Solutions.

In fact, the combined investments by ABP, PFZW and GPIF in meatpackers JBS, Marfrig and Minerva outweigh the 2.2 billion reais ($402 million) that U.S.-based BlackRock, the world’s biggest asset manager, has invested in those companies, according to an investigation by Brazilian investigative journalism outlet ((o))eco. JBS, Marfrig and Minerva have been ranked as first, fifth and 10th, respectively, among the beef producers with the greatest exposure to deforestation in the Amazon, according to a study by Imazon, a Brazilian research institute.

The ((o))eco study is based on pension fund data analyzed by Forests and Finance, a coalition of NGOs that investigates financing associated with the destruction of tropical forests. For its investigation, ((o))eco looked deeper into the numbers to determine the total investment by each of these three pension funds with the highest exposure to the Brazilian meat industry.

ABP, the pension fund for Dutch government workers and educators, tops the list with total investments of $219 million nearly 90% of it in JBS, the world’s biggest meatpacker.

“One in every six people in the Netherlands does or will receive retirement funds from ABP,” the organization says on its website.

Japan’s GPIF, the world’s largest pension fund, catering to the country’s public servants, has $188 million invested in the three Brazilian meatpackers. More than 90% of this is invested in JBS.

The Netherlands’ PFZW, the pension fund for workers in the social and health industries, has $163 million invested among JBS, Marfrig and Minerva.

The Netherlands is one of the nations that has been the most critical about the increasing rate of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. In June last year its parliament approved a motion against the free-trade agreement between the European Union and the South American trading bloc Mercosur (known in Brazil as Mercosul). Other EU governments have also expressed reservations about ratifying the trade deal in light of the environmental policies in Brazil, South America’s biggest economy.

Yet despite these expressions of concern, two of the biggest pension funds in the Netherlands continue to be among the biggest known investors in meatpackers whose industry is responsible for some 80% of the deforestation in the Amazon.

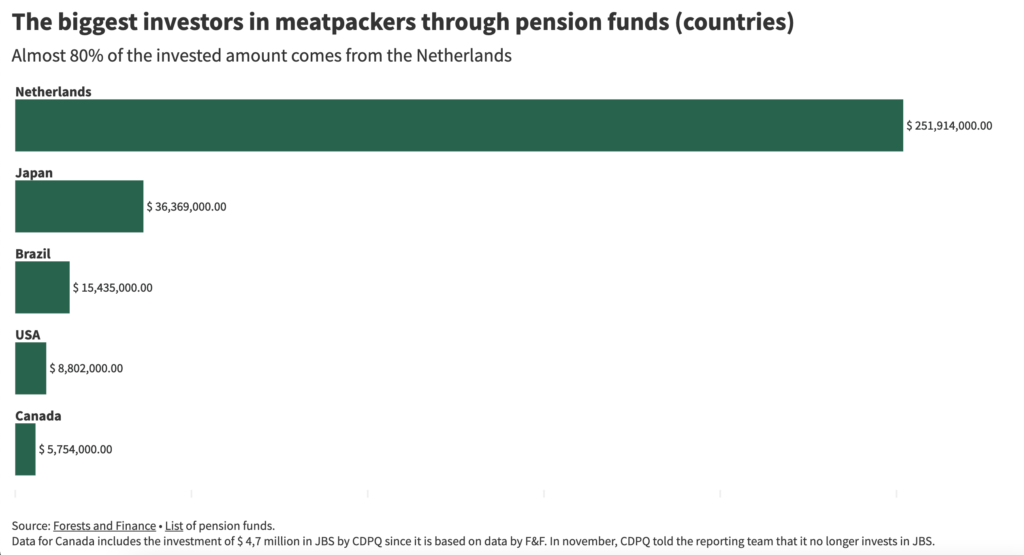

According to Forests and Finance, 79% of pension fund investments in JBS, Marfrig and Minerva come from the Netherlands. Japan comes in second and Brazilian pension funds third.

More exposure for domestic funds

In Brazil, 300 pension funds administer a combined 981 billion reais ($180 billion) — an amount equal to 13% of Brazil’s 2019 GDP. The largest are connected to Brazil’s biggest state-run companies: Banco do Brasil and Caixa Econômica Federal, both banks, and oil and gas firm Petrobras.

These domestic funds allocate only a small share of these resources into the beef industry, but that’s more a result of economic pragmatism rather than any sense of environmental consciousness.

More than 60% of the assets administered by Brazilian pension funds go toward buying government bonds, according to federal pension fund regulator Previc. These are seen as a low-risk security with little chance of default, says Norberto Montani Martins from the Institute of Economics at Rio de Janeiro Federal University.

“The government will always be able to issue currency to pay its obligations,” he says.

Banco do Brasil’s pension fund, Previ, told our reporters that it holds $54 million in total shares of JBS, Marfrig and Minerva. Caixa’s pension fund,

Funcef, has $31 million invested in the meatpackers, nearly 90% of it in JBS stock. Funcef did not respond to our requests for comment; the data are from its most recent annual report, 2019.

Link to visualization

Petrobras’s pension fund, Petros, only invests indirectly in the meatpackers, i.e. when the retirement funds are invested in another fund, which then invests in a group of companies.

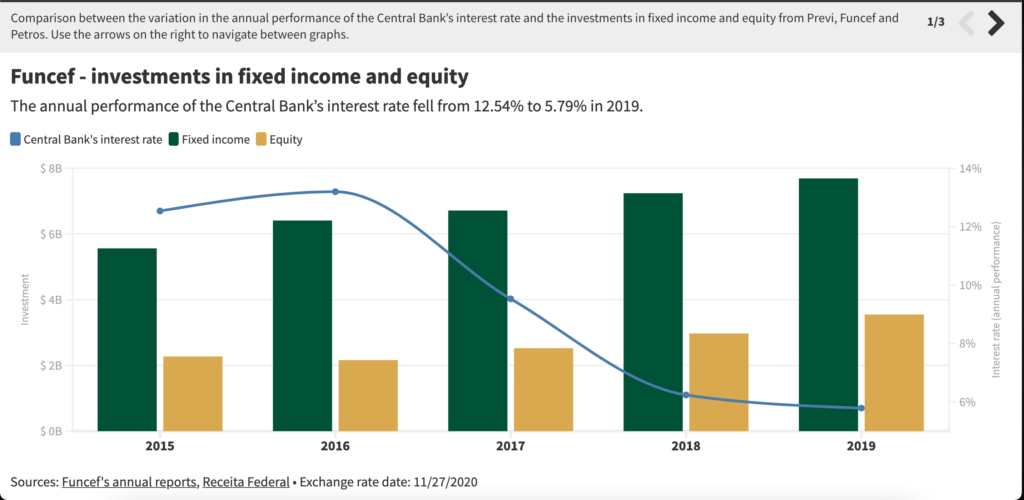

But the situation may soon change. The Brazilian central bank’s key interest rate has fallen from nearly 25% at the beginning of the 2000s to a record low of 2% today. This steep decline is forcing fund managers to seek out higher-risk investments.

“International interest rates have always been lower, which is the reason that pension funds in other countries have invested much more in stocks and real assets of the economy than in fixed income, sovereign or government bonds,” says Gustavo Pimentel, director of SITAWI, an organization that promotes responsible investment in Brazil. “When the interest rate drops in Brazil, it begins to get more difficult for national funds to hit their targets by investing in fixed income alone. So they start moving, investing more in stocks, real estate, real estate funds, equity funds, private equity.”

Banco do Brazil’s Previ has already taken action. “There will be a natural movement to substitute fixed income titles with other types of assets like stocks, real estate and overseas investments,” says Marcelo Wagner, the bank’s director of investments. “Even for us, this diversification will intensify,” he adds, saying the process could take years.

https://flo.uri.sh/story/739389/embedThis shift in outlook by Brazilian pension funds puts them at greater exposure to environmental risk via increased investments in the beef industry. This is because companies in this industry are included in numerous indexes formulated by the capital market to guide investments. JBS, Marfrig and Minerva are part of Ibovespa, the index that serves as the main reference for investors in the Brazilian capital market. They’re even featured in the ostensibly “green” indexes, receiving millions in investments through their listings on the “carbon efficient” and “sustainability” indexes on B3, the Brazilian stock exchange. Marfrig and Minerva were recently added to the select list of companies that, aside from being lucrative, are touted on the market as being environmentally responsible — regardless of their high exposure to deforestation in the Amazon.

Brazilian legislation, meanwhile, is not clear enough to require pension funds to consider environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria in their investment decisions. Resolution 4.661 from 2018 requires that entities should consider these risks “whenever possible.” Instruction number 6, issued a few months later, attempted to address this, but there are still gaps through which ESG criteria can be ignored.

“The law is a little more explicit and has nudged the funds toward ESG risk analysis,” Pimentel says. “Some have already woken up to this new scenario, but others will keep claiming that it is impossible.”

Deforestation not a top concern

Unlike in Brazil, the capital markets in the Netherlands have quite advanced criteria for measuring the social and environmental impacts of investments. “The leading ESG pension funds globally are those from Netherlands, France, Scandinavia and California,” Pimentel says.

The Netherlands has a strong reputation for its environmental consciousness: the country is famous for the widespread use of bicycles for individual transportation, and ranks second on The Good Country Index, which measures how much a nation contributes to the rest of the world.

But even there, tropical deforestation isn’t the top concern regarding global warming.

ABP, for example, says it has reduced its portfolio’s carbon footprint by 37% since 2015. “Sustainability isn’t optional for ABP. We really want to contribute to a world that is pleasant to live in,” the fund says. At the same time, it continues to invest in JBS, Marfrig and Minerva — a contradiction, given these companies’ leading roles in an industry that’s one of the top emitters of greenhouse gases in Brazil.

Globally, cattle ranching is responsible for around 9% of greenhouse gas emissions; in Brazil, one of the world’s top producers of beef, it accounts for 19% — and may be as much as 45% if emissions resulting from deforestation are included in the calculation. ABP says it recognizes that “deforestation carries financial risk for the food companies in which we invest,” but doesn’t cite either the beef or the cattle farming industries — the greatest risk to the Amazon — in its latest report on responsible investment.

It’s a similar picture at PFZW. The fund’s senior consultant on responsible investment, Piet Klop, says PFZW prioritizes CO2 reduction in the three sectors with most exposure in its portfolio, but none of these includes Brazilian cattle ranching.

“The link between deforestation and climate risk still isn’t very clear,” says Natalie Unterstell, the public administrator and director at Talanoa, an organization that produces climate risk mitigation studies and projects. “When we tell investors that they will lose money on the medium-term with oil and fossil fuels because these assets will run aground, they know exactly which financial asset we are talking about. With deforestation, it’s much more diffuse,” Unterstell told ((o))eco in June last year.

Investor engagement vs divestment

ABP acknowledges that its beef industry investment policy is not explicit, but says it makes “regular contact with JBS and other companies to pressure them to make anti-deforestation policies including mapping of their supply chain.”

“This allows us to put on the screws and really change something. If we sell the shares, another investor who may be less sustainable, could buy them and nothing will change,” the fund says.

PFZW says it uses a similar strategy of engagement to drive change.

“Progress is slow, but at least we are moving in the right direction,” Klop says. “We don’t see an effective alternative to this in influencing companies to do better. Exclusion would simply eliminate the small amount of influencing power we may have.”

It was thanks to this kind of pressure that JBS and Marfrig recently announced their commitment to track their entire supplier chains by 2025. Minerva began a pilot project to evaluate the risks related to its indirect suppliers. Prior to this, the meatpackers would only guarantee compliance with environmental and sustainability standards from the last farm through which its cattle passed before being slaughtered. But for each direct supplier, there are five to 10 indirect ones — blind spots in the environmental monitoring system. JBS, Marfrig and Minerva had already promised full supply chain tracking in 2009. Twelve years on, aside from admitting they did not fulfill their promise, JBS and Mafrig are giving themselves another four years to resolve the problem. Minerva has yet to set a deadline for itself.

Marcelo Seraphim, head of Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) in Brazil, an initiative of investors committed to social and environmental sustainability, also says that dumping shares in problematic companies is not the solution.

“The responsible investor can buy products that are harmful to the environment as long as he engages with the company to reduce its negative actions. And the Dutch investors are very active in terms of pressuring companies to improve their performance,” he says.

But there are alternatives to engagement. In July last year Finnish fund manager Nordea sold 240 million reais ($44 million) in JBS shares because of the company’s association with deforestation and COVID-19 outbreaks at its plants in Brazil and the U.S. The Norwegian government’s pension fund had already excluded JBS stock due to risks related to corruption; in August 2020, it added Eletrobras and Vale, the Brazilian power utility and the country’s biggest miner, to the list. It cited the social and environmental impacts from the construction of the Belo Monte hydroelectric dam in the state of Pará, and the deadly collapse of tailings dams in Brumadinho and Mariana in the state of Minas Gerais.

At least one pension fund has divested from the Brazilian meatpackers. Canada’s Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (CDPQ), the pension fund for more than 2 million Quebec residents, held $4.7 million in JBS stock in December 2018, according to the Forests & Finance study. Today the fund says it no longer holds any JBS shares. In a statement to ((o))eco, CDPQ said: “Climate change is integrated into CDPQ’s entire decision-making process. After careful analysis, we concluded that JBS is not a company in which we want to own stock.”

Climate change a long-term threat

Aside from ethical or reputational risks, investing in companies that harm the environment can generate real financial risks. The climate crisis is already altering natural cycles and will have concrete impacts on sectors like agribusiness, where JBS, Marfrig and Minerva operate. If companies don’t know how to react quickly, they will suffer losses.

This is a problem that pension funds, whose planning is for 20, 30 and 40 years out, can’t ignore. “Pension funds would have the greatest interest in considering ESG criteria in their management because when we talk about ESG, we are talking long term,” Seraphim says.

Fitch’s Cole Martin says pension funds, especially those in Europe, are aware of the risks associated with not considering ESG criteria, but have been very slow to put them into practice. He quotes a study that analyzed 927 institutional investors in 12 countries. It showed that while 88% of pension funds mention ESG criteria in their investment policies, fewer than one in 10 have created specific departments to work on responsible investing.

Martin says one of the reasons for the gap between rhetoric and action is the conservative profile of pension fund clients. “If a young person loses her money in an investment, she has the rest of her life to recuperate it. Her fixed costs are also much lower than pension fund beneficiaries, who tend to be older and retired and dealing with costs related to family, real estate financing and possibly medical costs. This is why these investors are less receptive to big changes to investment strategy on the part of their pension funds,” he says.

The structure of pension funds also makes the process of incorporating ESG criteria more difficult. “They are large, very bureaucratic structures that take a very long time to change,” Martin says.

This pragmatic posture is reflected in PFZW’s approach. “We work so that the pension fund achieves its main objective: to pay for retirement,”says Klop, the funds consultant. “While we try to provide these retirements with as little negative impact as possible (ESG), we cannot administrate our assets with an eye only on solving the world’s problems (or Brazil’s).”

Paradoxically, this low tolerance for risk could prove costly for the beneficiaries, not just because of the long-term profile, but also because of the size of investments.

“If you are large and find you have an asset carrying ESG risk in your portfolio and want to get rid of it, it takes time,” says SITAWI’s Gustavo Pimentel. “You can’t do it overnight. The larger you are, the more exposed you are to market risks in general, including ESG risks.”

Greater ESG discourse

With an eye on these risks, the European Union has been trying to speed up the financial sector’s adaptation process to climate challenges through EU Taxonomy, a guide that classifies economic sectors according to their environmental impact and creates a standard measure for comparing the sustainability of each one. Starting in December of 2021, all EU financial institutions, including pension funds, will have to include this green indicator when reporting where they invest their resources. In the United States, by contrast, the government has moved to unwind environmental requirements for financial companies. In June last year, the Department of Labor proposed a ruling that would prohibit pension funds from considering ESG criteria in their investment decision-making. “Private employer-sponsored retirement plans are not vehicles for furthering social goals or policy objectives that are not in the financial interest of the plan,” said Eugene Scalia, the labor secretary at the time.

The Department of Labor gave a 30-day period for members of the public to express their opinions on the proposal. During this time, it received more than 1,500 letters criticizing the idea, sent by investors, asset managers, trade unions and other organizations.

With Donald Trump now replaced by Joe Biden as president, the controversial move is not expected to proceed. The Democrat agenda includes a climate plan of action to leverage a more sustainable economy, while Biden has also brought the U.S. back into the Paris Agreement, reversing another Trump administration move. Seraphim says that while the Trump administration’s labor department proposal “is a huge setback … I believe that the discourse on sustainability will change in the U.S.”

“Talks will become more reasonable and it will turn around,” he adds.

Responses

Petrobras’s Petros fund declined to comment to ((o))eco for this story. Caixa Econômica Federal’s Funcef fund did not respond to our inquiries. We were unable to speak with anyone at the Japanese Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF).

Netherlands-based Algemeen Burgerlijk Pensioenfonds sent a response that can be read in full here(sent from the press office at APG, which administers its investments). Pensioenfonds Zorg en Welzijn’s response can be read here; from Brazilian pension fund regulator Previc, here; and from Banco do Brasil’s pension fund, Previ, here.

Translated by Maya Johnson

Illustrations by Julia Lima