News

Are banks turning a blind eye to profit shifting in Indonesia’s forestry and plantation sectors?

Industry groups representing Indonesia’s forestry and plantation sectors regularly portray their environmental impacts as trade-offs inherent in Indonesia’s economic development. Corporate tax revenues generated are frequently cited as evidence of contribution to national development, and groups like pulp & paper giant APRIL have widely publicized headline tax payments to demonstrate its positive economic impacts.

A recent report suggests that such claims warrant intense scrutiny. The Macao Money Machine, published in November by a group of Indonesian and international groups under the banner Tax Justice Forum (Forum Pajak Berkeadilan), details how two pulp divisions of Royal Golden Eagle (RGE) group apparently both shifted hundreds of millions of dollars in taxable profits out of Indonesia, to the Chinese tax haven of Macau.

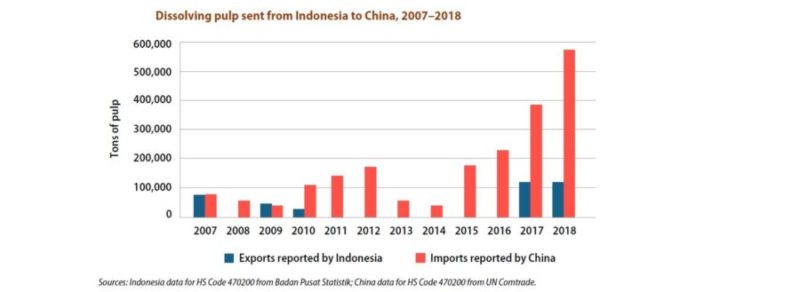

Based on anomalies in trade data and the disclosures in company annual reports, it describes how RGE’s two pulp producers – Toba Pulp Lestari Tbk (TPL) and APRIL both exported huge volumes of high quality dissolving pulp used in fabric manufacturing, while declaring to Indonesian customs that it was much less valuable paper-grade pulp. This is like exporting cream and telling customs its milk. The misidentified pulp exports were purchased by an RGE affiliated company in Macao, which then marketed the product in China as the higher value dissolving pulp, thereby booking the profit in low-tax Macao.

The report authors estimate that, using this mechanism, RGE’s pulp divisions underreported their revenues by USD $668 million over the 2007-2018 period. Based on statutory corporation tax rates, the authors state that the underported amount may have generated around $168 million in state revenues (though they make clear that they do not know the overall tax situation of the companies and their effective tax rates). To get a sense of scale, RGE’s TPL operation reported paying a total of USD 16 million in taxes over nearly a decade (2007-2016). While PT RAPP (the largest pulp producer under RGE’s other pulp division APRIL) reported paying a total of USD 183 million over nearly twenty years (1999-2017).

Whether this type of misreporting and profit shifting is legal or illegal depends on a number of factors. Key is whether transactions between operations in Indonesia and affiliated trading companies in offshore tax havens follow the “arm’s length principle”. Simply put, this means that the buying and selling of commodities must be conducted as if the buyer and seller were unrelated parties, acting in their own self-interest. Another factor that could determine legality is whether the pulp product misidentified in the invoices were deliberately falsified (known as trade misinvoicing, which is illegal in Indonesia and most other countries).

In response to the allegations, Toba Pulp Lestari stated that it has produced and sold products at appropriate prices, and that it always upholds Good Corporate Governance and carries out its activities in accordance with prevailing laws and regulations. APRIL stated that its dissolving pulp exports were paper-grade pulp as the product was still in a trial development stage and therefore exported under the less valuable HS Code.

This is not the first time that RGE and its principal owner, the oligarch Sukanto Tanoto have been embroiled in a tax scandal. Back in 2012, RGE’s palm oil division Asian Agri was found guilty of tax evasion and fined US $200 million after a whistleblower revealed details of routine and systematic fraudulent accounting practices. That case had striking similarities involving transfer pricing and offshore companies.

Governance Risks and Abusive Tax Arrangements

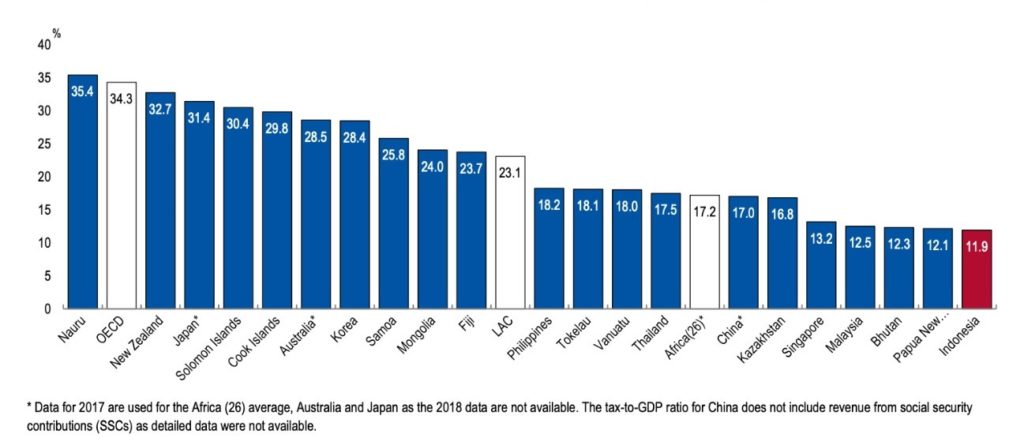

As Figure 1 shows, Indonesia has the lowest rates of tax revenue collection among its emerging market and regional peers, with a tax-to-GDP ratio of 11.9% in 2018. Profit shifting practices by multinationals are a major factor in Indonesia’s chronic tax collection problems. Indonesia’s Ministry of Finance estimates that such practice resulted in USD 15.6 billion state losses in 2015 alone, largely in the natural resource and commodities sector. Global Financial Integrity estimates that US$ 6.5 billion flowed out of Indonesia in 2016 through trade misinvoicing (which involves deliberately falsifying invoices).

Figure 1 – Asia Pacific Tax-to-GDP ratios and global comparisons (2018, source: OECD)

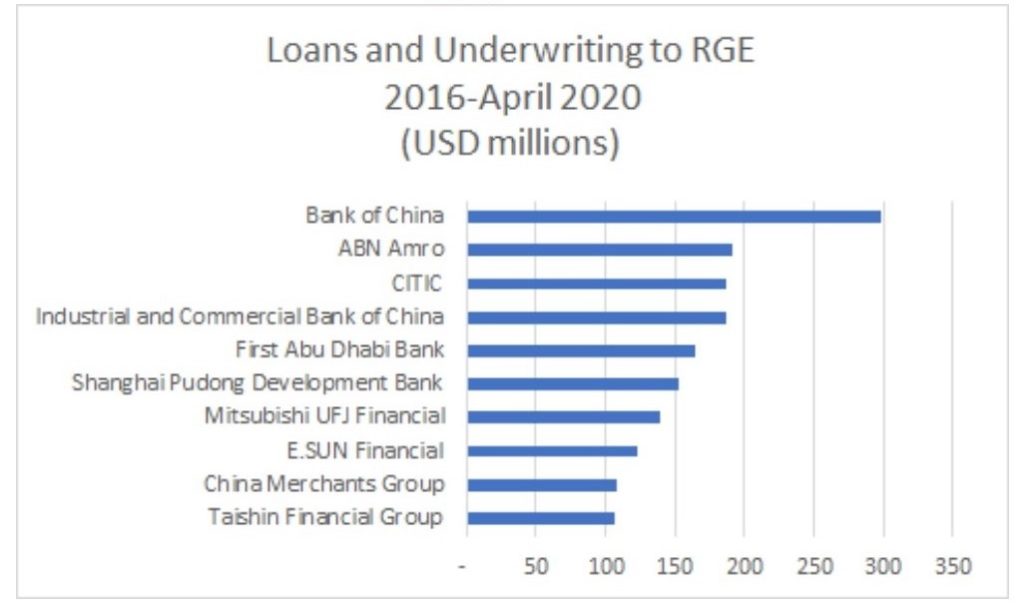

Yet Forests & Finance policy analysis of 31 banks financing the forest-risk sector shows that only three banks – ABN Amro, Rabobank and BNP Paribas – have any governance safeguards that mitigate against risks related to tax avoidance and evasion.

Figure 2 – GRAPH SHOWING RGE PULP & PALM FINANCIERS

Only one of RGE’s financiers, ABN Amro, has a publicly-available policy addressing tax-related governance risks. While it may seem paradoxical, banks majority-owned by the Indonesian state do not have public governance policies that prohibit clients’ use of abusive or even illegal tax schemes, despite the Indonesian state losing out on billions of dollars in tax revenues every year.

What should banks do?

Banks must publicly commit to tackling profit shifting practices that rob developing countries of much-needed tax revenue. They can start by introducing robust policies to mitigate tax-related governance risks posed by their clients, which are especially acute in the natural resource sector. These policies must explicitly prohibit abusive tax arrangements, transfer pricing, and trade mis-invoicing.

Indonesia’s new and controversial Omnibus Bill on Job Creation aims to attract investment by slashing corporate tax rates further still (alongside many other sweeping deregulatory measures). Unless there are major efforts by the Ministry of Finance and Customs to stop multinationals shifting profits offshore, Indonesia could see its tax-to-gdp ratio drop even further.

There is near consensus among finance ministries and multilateral institutions like OECD and the IMF, that tackling abusive transnational tax schemes is critical if countries are to deliver on their Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).