News

Cargill: Violating Indigenous Peoples’ and traditional communities’ rights in Brazil

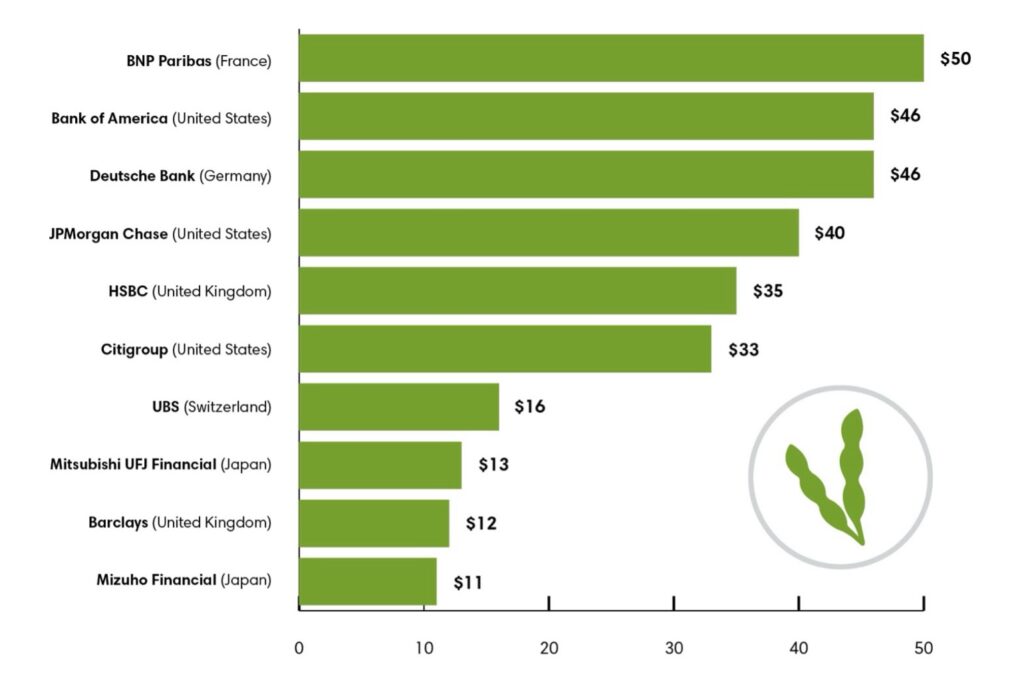

Cargill has been supported by some of the worlds’ largest banks, despite an extensive legacy of human rights abuses and environmental degradation. Since 2019, Cargill has received US$ 473 million in credit for its soy operations in tropical forest regions. The value of these forest-risk soy-attributable credit flows has fluctuated significantly throughout the period, with peaks of US$ 136 million in 2019 and US$ 176 million in 2021.

Largest 10 creditors to Cargill’s soy operations (2019-2023 September, US$ millions)

Cargill is one of the largest agricultural companies in the world and the largest privately held company in the US, with a revenue in 2023 of $ 177 billion. They are a major exporter of soy from Brazil and have been linked to a litany of deforestation and human rights violations for decades. In 2023, a civil society campaign, Burning Legacy, was launched to hold Cargill accountable for its unacceptable business practices. Over 100 case investigations have been compiled, documenting ample evidence of human rights abuses and deforestation in Cargill’s supply chain.

Despite committing to zero deforestation by 2020, Cargill failed to meet this goal and has since refused to sign a soy moratorium for the Cerrado. It is now expanding its operations to further exploit the Brazilian Amazon and the Cerrado. These huge biodiverse biomes are highly sensitive to disturbance, and both play critical roles in stabilizing the climate and regulating the water cycles in the region. While deforestation rates in the Amazon fell by 42% during the first seven months of 2023 compared to the same period in 2022, in the neighboring Cerrado savanna there was a surge, entirely due to the expansion of land speculation and agribusiness.

Deforestation rates in the Cerrado have been increasing since 2019 and are now three times the rate of deforestation in the Amazon. The Cerrado, which makes up some 23% of Brazil’s entire territory, contains up to 5% of the world’s plant and animal species, making it the world’s most biodiverse savannah. The depletion of this biome, known as Brazil’s “birthplace of waters,” poses a serious risk to the watersheds in South America that many people and thousands of endemic species depend upon for habitat, sustenance livelihoods, and a safe climate.

Forest and biodiversity destruction for soy

Brazil is the largest producer of soybean in the world, producing 135 million tonnes of soy in 2021. Soy is the second largest driver of deforestation and land conversion in Brazil. Forests are cut for soy production, but soy production also expands into former cattle pastures, pushing cattle ranching further into forests. Infrastructure to expand soy capacity in Brazil has been developing rapidly since 2006, with roads, railways, and ports opening up large swaths of the Amazon and Cerrado to industrial agriculture. One of the latest projects includes the now suspended Ferrogrão railway, which, if constructed, would facilitate the export of soybeans produced in the Cerrado through ports in the Amazon. It would affect at least six Indigenous lands, 17 conservation units, and three isolated tribes.

The major traders Cargill, Bunge, and ADM have been behind much of the expansion. Their many port developments continue to threaten the lives and livelihoods of Indigenous and traditional communities and violate their FPIC rights. Cargill is pushing through a river port in Abaetetuba, Pará, located on the Amazon river. If built, the port is expected to cause serious damage to the river ecosystem, impacting local fishing communities. According to the 2018 Environmental Impact Assessment, it would handle up to 9 million tonnes of soy and other grains each year from the states of Pará, Maranhão, Piauí, Tocantins, Rondônia and Mato Grosso, ultimately incentivizing soy expansion.

Another key driver of soy-driven deforestation is the financialization of land itself. With soy markets growing ever more lucrative, land grabbers, gunmen, and militias violently steal land from local communities, falsify land titles, and subsequently deforest the land in preparation to sell or lease it to agribusiness interests, whose soy inevitably enters the supply chains of large multinational soy companies. In this way, the financial sector itself is directly implicated in creating the enabling conditions for ecosystem destruction.

Defending Indigenous and traditional lands

In October 2023, Beka Saw Munduruku, an Indigenous leader from the Sawre Muybu village of the Brazilian Amazon, hand-delivered a letter to the Cargill family. She called on the company to stop the destruction of their lands and their forests, which are under threat from Cargill’s aggressive and unceasing soy expansion. The letter stated that her community has been fighting to defend their land against Cargill for many years but has faced violence and intimidation.

In Abaetetuba, the land earmarked for the soy port has been recognized as a traditional territory (Projeto de Assentamento Agroextrativista). The communities claim Cargill is grabbing their land, and they are fighting for their rights in court. In May 2023, the state public defender (Defensoria Pública do Estado) accused Cargill of violating the rights of the impacted communities and recommended the suspension of Cargill’s license. This was followed by the public prosecutor’s office (MFP), who called for the project to be suspended in June 2023 when they alleged Cargill was land grabbing and called for the federal court to review the FPIC process because it impacts federal lands and a river. The federal prosecutor launched a criminal probe into the acquisition of the land in October 2023.

The environmental and social issues in Cargill’s planned port in Abaetetuba are not new or confined to just this project. Investigations published by leading environmental and human rights law nonprofits have found a continued failure to clean up its supply chains or to comply with national laws on Indigenous Peoples’ rights. Client Earth has alleged in a complaint to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) that Cargill is violating Indigenous Peoples’ rights by failing to conduct adequate environmental or human rights due diligence on its soy supply chains and operations in Brazil.

Cargill already operates two ports in the Amazon: one in Santarém and the other in Itaituba (both in the state of Pará). Both ports have caused significant impacts. Brazilian human rights organization Terra de Direitos has found that Cargill has failed to comply with socio-environmental regulations for both ports. They found that, among other issues, Cargill failed to consult Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the development of these ports, violating their right to give or withhold Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) to issues affecting their lives and lands.

In response to allegations of violating the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in its port development, Cargill stated that it has complied with the requirements of the licensing body. Cargill further states that it is committed to be deforestation-free in its soy and palm supply chains by 2025.

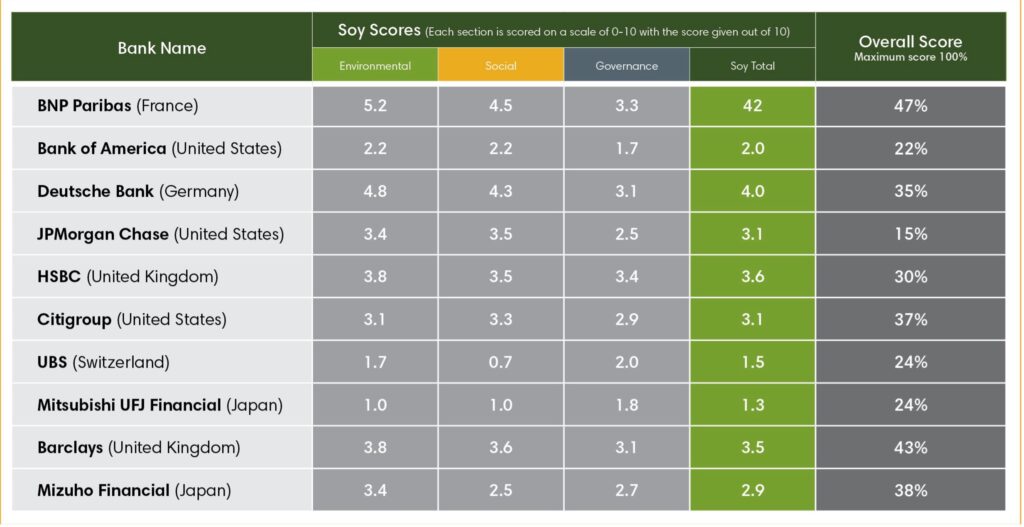

How do the policies of Cargill’s bankers stack up?

Cargill’s forest-risk creditors covered in this report all score under 50% overall, and also for the soy sector policies, indicating they are failing to acknowledge and effectively mitigate the risks associated with their financing in Brazil. An overall score of 5 out of 10 means that the financier does not have an adequate policy without loopholes on all the environmental, social, and governance risks related to deforestation.

BNP Paribas, the largest Cargill creditor, has the highest overall score, at 47%, and 5.2 out of 10 for environment criteria for the soy sector. These policy commitments, coupled with the bank’s position as ninth largest financier of forest-risk commodities, raise questions about the effectiveness of the bank’s policy implementation. Banks scoring 3 and above out of 10 do have some level of ESG policy commitments, which should alert them to Cargill as a high ESG-risk client warranting enhanced due diligence.

Four banks scored below 25% overall: JPMorgan Chase (15%), Bank of America (22%), MUFG (24%), and UBS (24%). All of these banks rank in the largest 30 forest-risk bank or investor league tables, which means they are highly exposed to environmental and social risks and impacts. Only two banks, European BNP Paribas (4.2) and Deutsche Bank (4.0), scored 4 or above out of 10 for their soy policies. The lowest scores for soy were by MUFG (1.2), UBS (1.5), and Bank of America (2.0) out of 10, which means their policies for soy would certainly fail to protect forests or prevent human rights abuses.

There are also some loopholes which make the policies weak and potentially ineffective for preventing harms in the forest-risk sectors. For example, Bank of America’s policies for No Deforestation and FPIC rights of Indigenous Peoples contain limiting language that means these policies only apply to project-specific financing, which plays only a minor role in these sectors. It is clear that these banks are lagging behind international best practices on environment and human rights.

Policy scores of Cargill’s largest soy creditors