Notícias

Can Malaysia’s financial sector rein in the country’s oil palm linked deforestation?

The governments of Malaysia and Indonesia are anxious to decouple palm oil’s association with deforestation and climate change. Palm oil prices have been tumbling for two years, and many analysts believe this isn’t just caused by a cyclical oversupply, but by the enduring concerns about its environmental and social impact, and inherent substitutability for other oils.

Soon after taking over as Malaysia’s Primary Industries Minister in early 2019, Teresa Kok embarked on a public relations drive to improve the image of Malaysian palm oil, claiming the government would limit further plantation development at the expense of forests. The details of this policy were announced in March 2019, and limit oil palm cultivation to 6.5 million hectares by 2023 (current planted area is estimated at 5.8 million hectares).

This means the development of a further 700,000 ha of plantations, which will most likely to occur in Sarawak, Malaysia’s largest state, which has long recorded extremely high rates of deforestation, peat development and widespread conflict between palm oil companies and customary landowners. Malaysia’s federal system grants the Sarawak State Government – whose politics has for decades been dominated by logging and plantation tycoons – autonomy over land and forest resources.

It appears that Sarawak plantation interests have built in a comfortable buffer for business as usual. Remote sensing and field data indicate that deforestation and peat development is likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

For example, publicly listed Bintulu Lumber Development Bhd (BLDPLNT: KLS)- controlled by the influential Lau family – reportedly developed over 3,000 ha peat forest in Sarawak during 2018. Another influential business family, the Ling family who control Shin Yang group and listed Sarawak Oil Palms Bhd (SOP: KLS) also continued to develop peat land into plantations in January 2019. While the privately held Double Dynasty group is razing forests near the boundary with a UNESCO World Heritage Site Mulu National Park. See powerful drone footage of this here.

Such operations pull the rug out from under federal government, who want to portray oil palm linked deforestation as a thing of the past. Unfortunately, the inability of the Malaysian federal government to halt deforestation in Sarawak affects the reputation of all Malaysian palm oil exports, including those companies who may genuinely be trying to make their businesses more sustainable.

So how else can the federal government transform the palm oil industry? An obvious tool is Malaysia’s financial sector.

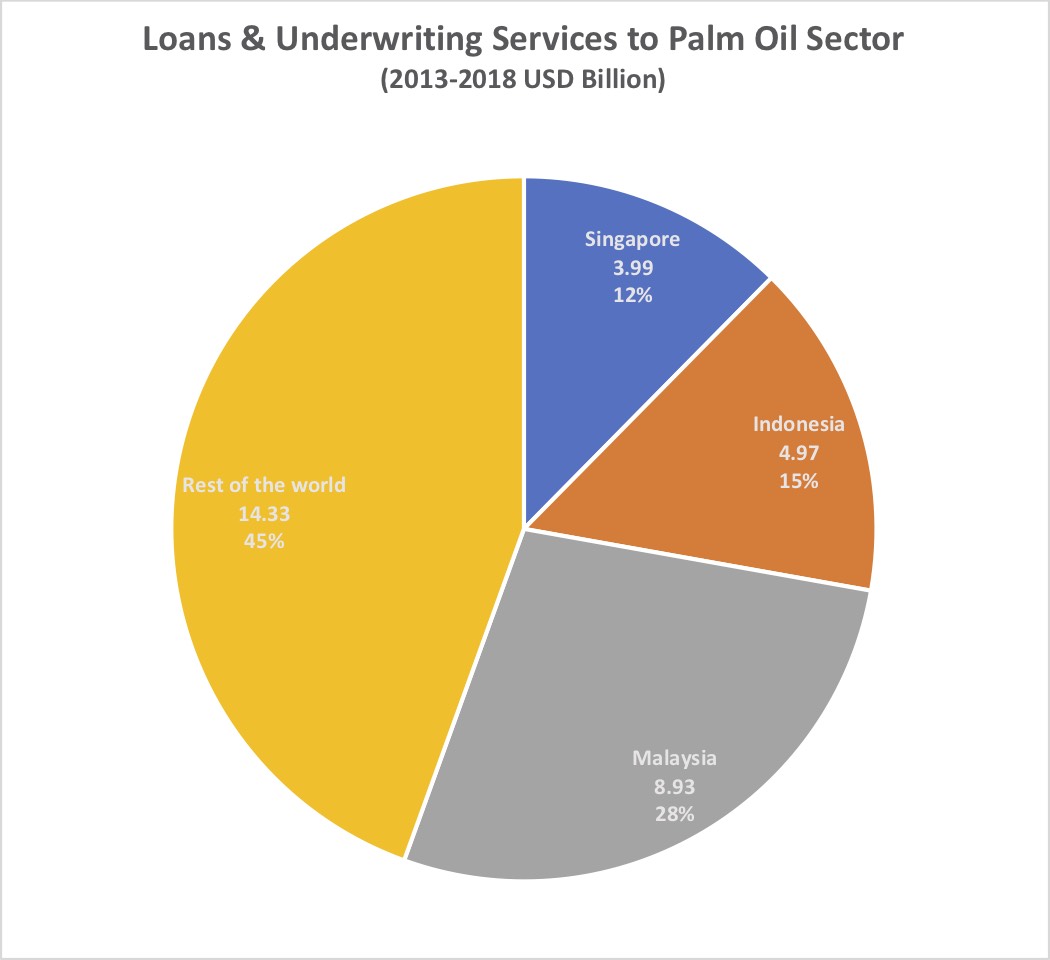

Forests and Finance data shows that Malaysia is now the biggest national financier of the global oil palm industry. Over the past 5 years, Malaysian financial institutions alone provided more than a quarter (28%) of all loans and underwriting services to palm oil companies, almost twice as much as Indonesian financial institutions which provided 15%.

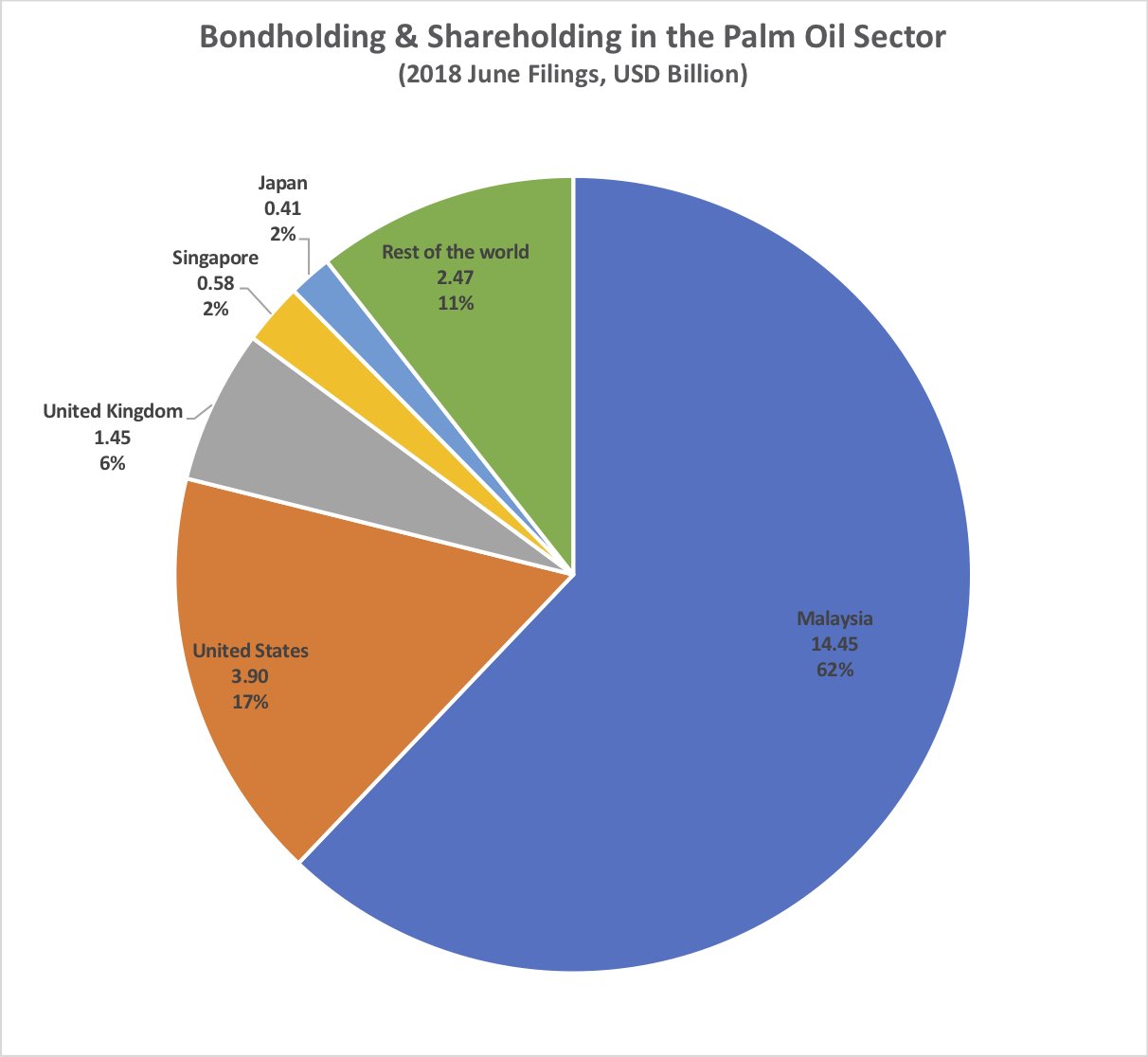

Moreover, in 2018 59% of total investments (bond and shareholdings), were made by Malaysian financial institutions, including among the top 3, large government linked entities such as PNB (USD 7.8B), EPF (USD 3.6B) and KWAP (USD 1.5B).

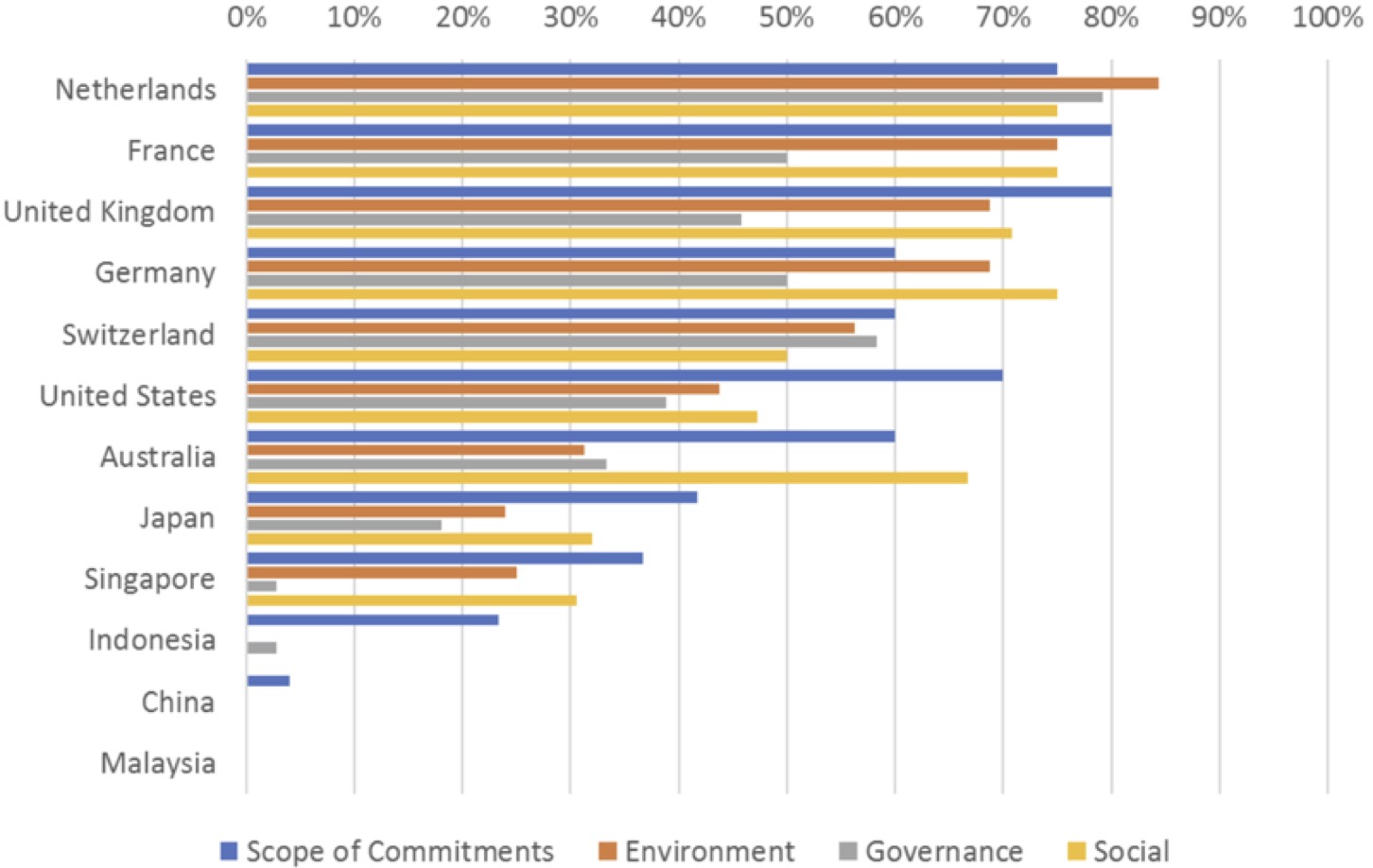

Based on the Malaysia financial sector’s heavy exposure to the palm oil industry, it would be in Malaysia’s economic interest that its financial institutions have adequately accounted for investment risks. Yet its financial sector ranks lowest of all countries surveyed in regards to policies and processes to measure and manage associated investment risk. . Properly analysing and managing Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) risks enables financial institutions to restrict finance to bad corporate actors and incentivise sustainable operators. Forest & Finance research shows that Malaysian banks and government-linked investment funds (taken as a national average) scored 0 on all four categories (scope of commitments, environmental, social and governance safeguards). This ranks Malaysia below regional peers China, Singapore and Indonesia.

National Average Policy Assessment Scores (2018)

For example, BLD Plantations (responsible for recent large-scale peatland development- see above) has been predominantly financed by Malaysian financial institutions such as RHB and Maybank, who have provided loans and underwritings of USD 69M in the past three years. Both of these banks scored an ignominious 0 points in our policy assessments, meaning they have no forest-risk sector policy, and lack any ESG safeguards to address the impacts of its clients like BLD.