Actualités

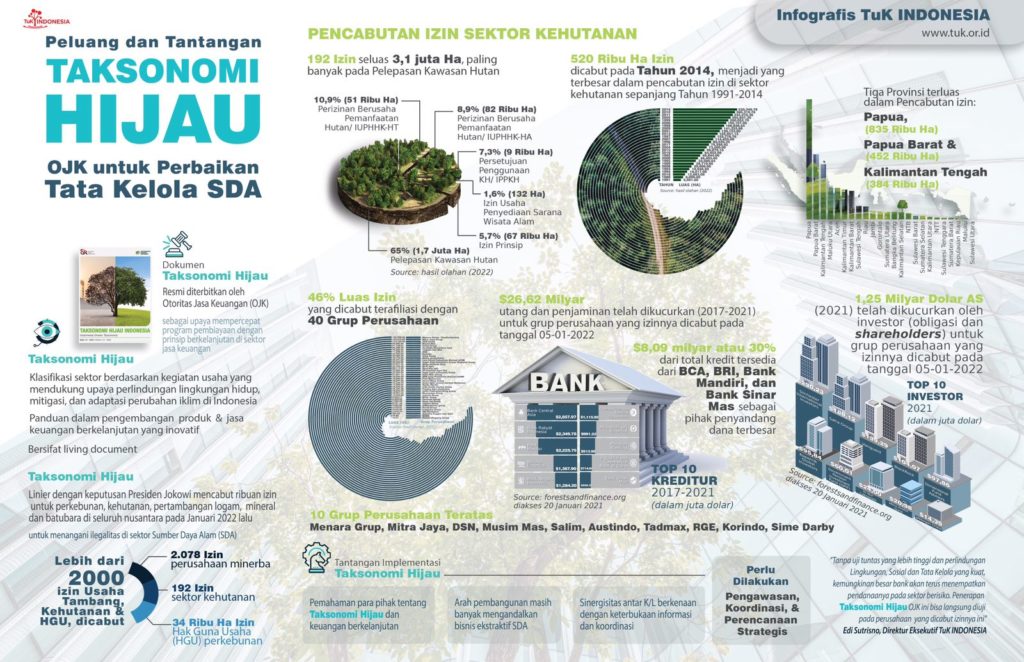

Défis et opportunités pour la taxonomie verte d’OJK dans l’amélioration de la gouvernance des ressources naturelles en Indonésie

Civil society is demanding that financiers stop funding palm oil and forestry companies whose permits have been revoked, and that the government be more transparent and accountable in its review and revocation of natural resource utilization permits.

Indonesia’s Financial Services Authority (OJK) today has officially released the Green Taxonomy document1 as an effort to accelerate sustainability-based financing in the financial service sector. This is much appreciated by civil society organizations which see it as a positive step taken by the Indonesian government to tackle illegality in the Natural Resources sector, in line with President Jokowi’s decree which revokes more than 2000 permits in the agricultural; forestry; and metal, mineral and coal mining sectors across the country in January 2022.

“All these events suggest material risks for banks exposed to forest-risk sectors such as palm oil and timber where illegality and non-compliance are rampant. Without higher due diligence and rigorous environmental, social and governance protection, it’s very likely that banks will continue investing in risky sectors. The application of OJK’s Green Taxonomy can be directly tested in companies whose permits have been revoked,” noted Edi Sutrisno, the Executive Director of TuK INDONESIA.

In the list of the companies2 whose permits have been revoked are three subsidiaries of Korindo which will lose substantial permit areas, amounting to more than 65,000 hectares of forest utilization concession: PT. Papua Agro Lestari (32,348 ha), PT. Tunas Sawa Erma (19,001 ha) and PT. Berkat Cipta Abadi II (14,435 ha). These areas have yet to be developed into plantations and include a vast area of primary forest. The revoked permit areas are equal to more than 40% of Korindo’s total concession areas, and such revocation will without doubt affect the group’s asset value. Indonesia’s state-owned Bank Negara Indonesia has, however, consistently reported that Korindo is among its top 10 clients in the agricultural sector, and the bank had outstanding loans to the group totaling USD 191 million in 2018.

“BNI should be very concerned about how its financing is exposed to high-risk companies, now with substantial stranded assets. Whatever the state’s decision is, financiers must respond to it,” said Edi.

It is, however, still unclear what has motivated the revocation and whether the revocation will help restore the land rights and end deforestation, or whether the revoked permit land will be transferred to other companies, perpetuating land grabs and conflicts with communities, and driving deforestation.

Regarding the evaluation process, the revocation of the HGUs (right to exploit) was carried out in secret and uncoordinated, suggesting that the process was not transparent and accountable. The government seemed to have arbitrarily chosen companies whose permits were to be revoked as we have not seen, to date, what assessment was used to identify which companies were to be evaluated and what indicators were used to justify the revocation.

In addition, civil society was excluded from the evaluation process – suggesting non-transparency and weak accountability in the process. Civil society has long been demanding that companies with outstanding issues be reviewed and their permits be revoked.

A large volume of reports have even been submitted to the government detailing activities of some companies on the ground. Such is done as part of civil society’s participation to improve governance of the natural resource sector.

“We’re questioning why companies with outstanding issues are still operating and their permits are not revoked,” noted Abdul Haris, Eastern Indonesia sustainability observer.

“Take Central Sulawesi as an illustration. Based on the recapitulation report of large-scale plantation companies in 2021, 608,987 hectares, spanning over 8 districts, were given as concessions to 52 large-scale companies, including large groups such as Astra Agro Lestari, SMART, Kencana Agri, BW Plantation, Cipta Cakra Murdaya, Sime Darby Plantation, Kurnia Luwuk Sejati, with the rest being unidentified companies. Of 49 palm oil permits, only 12 have been realized, the rest being uncultivated. These companies are affiliated with large groups, both Indonesian and overseas; even seven have obtained HGU (right to exploit),” explained Haris.

“What will become of the land and the forests in the revoked permit areas and the risks the revocation would pose to environmental and social rehabilitation are still unclear. Companies should remain accountable and rehabilitate degraded land, food sources and forests. We’re calling on the government to restore the rights of indigenous people to land and customary forests which have been violated (grabbed) through the granting of the permits and we’re urging the government to be transparent and to open room for the public to get involved in the governance plan of the revoked areas,” said Rudiansyah, a sustainability observer who focuses on land utilization in Sumatra, in particular Jambi.

Originally published by TuK Indonesia3

1 The Green Taxonomy is a living document containing guidance for innovative sustainable financial products and services. The document also lists sectors classified by business activities which support environmental protection and climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts in Indonesia.

2 Decree of Environment and Forestry Minister of the Republic of Indonesia

No:SK.01/MENLHK/SETJEN/KUM.1/1/2022 on Revocation of Forest Area Concession Permits.

3. Slides of the webinar on the Green Taxonomy (in Indonesian).